Church History

Author: Mykhailo Pryimych,

Translation: Mykhailo Syrokhman

The Church of the Protection of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Horiany Rotunda) is closely connected with the history and culture of Transcarpathia. The modern appearance of the church: a nave covered with a gable roof, the western facade topped with a small baroque tower, sacristy and sanctuary, – was formed during its reconstruction by the architect Ottó Sztehlo in 1912. It was at that time that the sanctuary-rotunda received a separate roof in the form of a helmet-shaped tent, and the sacristy was reduced by shifting its eastern wall to the west. The building consists of two parts built in differ time: a brick rotunda of the 13th century and stone nave and sacristy constructed in the 14th century.

The architecture of the nave allows to state that the building is related to the so-called provincial Gothic, which was actively developing in Transcarpathia in the 14th century. This stone structure shows some Gothic features, which are the pointed arch of the main portal, the form of the north portal, the framing of the south portal and the form of three windows. The construction of these provincial parochial churches is associated with the changes that took place in the medieval Hungarian kingdom, after the accession to the throne of the new ruler Charles-Robert, the founder of the Anjou dynasty. Thanks to his activities, the development of crafts and trade was intensified, and the invitation of German colonists had a noticeable effect on the development of architecture and its forms. Increasing at that time was the number of parochial two-partite stone churches (Horyany, Vyshkovo, Khust, Uzhhorod), which indicates the deepening of the processes of Christianization. The appearance of the church in Horiany is a witness that a community was formed and they needed a nave to be built. This fact is evidenced by a document according to which in 1334 and 1335 Horiany was mentioned as a parish that paid 2 groschen of the papal tithe.[1]

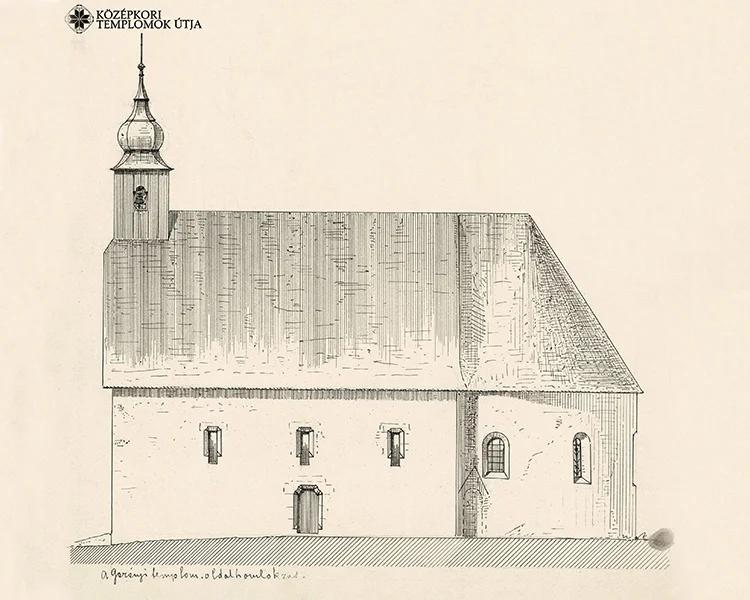

South facade before restoration (Otto Steglo, 1894) Photo taken by Attila Mudrak, source of archival materials: Forster Center, Scientific and Technical Archive, archive number: K 2776 Access: http://templomut.hu

Plan and section before restoration, reconstruction of the rotunda and a fragment of the cornice (Jožef Huska, 1900) Photo taken by Attila Mudrak, source of archival materials: Forster Center, Scientific and Technical Archive, archive number: FM 117 Access: http://templomut.hu

Plan and cross-section, plans for restoration (Otto Steglo, 1912) Photo taken by Attila Mudrak, source of archival materials: Forster Center, scientific and technical archive, archive number: K 2775 Access: http://templomut.hu

Outside view from the eastern side and cross-section (János Kladek, 1912) Photographs were taken by Attila Mudrak, source of archival materials: Forster Center, scientific and technical archive, archive number: K 2777 http://templomut.hu

Catholic church with a rotunda. Horiany (Uzhhorod), (Bohumil Vavroushek, 1929) Bohumil Vavroušek: Církevní památky na Podkarpatské Rusi (272 fotografií lidových staveb). Praha, 1929, il.1

Inside the church. Horiany (Uzhhorod), (Bohumil Vavroushek, 1929) Bohumil Vavroušek: Církevní památky na Podkarpatské Rusi (272 fotografií lidových staveb). Praha, 1929, il.2

Rotunda. Horiany (Uzhhorod), (Bohumil Vavroushek, 1929) Bohumil Vavroušek: Církevní památky na Podkarpatské Rusi (272 fotografií lidových staveb). Praha, 1929, il.3

Frescoes in the rotunda. Horiany (Uzhhorod), (Bohumil Vavroushek, 1929) Bohumil Vavroušek: Církevní památky na Podkarpatské Rusi (272 fotografií lidových staveb). Praha, 1929, il.4

Horiany: rotunda. T-H-1-176 (Rudolf Gulka, 1921) T-H-1-176, Horiany: a Rotunda, the oldest stone Church in Subcarpathia (today in Uzhhorod), built in the 12th century; the nave was added in the 15th century, 2021 The lost world of Subcarpathian Rus' in the photographs of Rudolf Hůlka (1887-1961). Praha: Národní knihovna České republiky - Slovanská knihovna, 2014.

In turn, the existence of a parish indicates the existence of a church, because the Ukrainian term 'tserkva' (church) rather corresponds to the Greek concept 'ekklesia' (Εκκλησία), which is translated as 'gathering'. Although the very sound of the word 'tserkva' also comes from the Greek 'kyriakon' (ϰυριαϰόν), which can be translated as 'house' or 'abode of God'. The word 'khram' (temple) corresponds to the same concept in Ukrainian. And since the Christian assembly – the church, – thought of the temple as a prototype of the universe, then each part of the structure carried an additional symbolic load.

Although the temple in Horiany consists of two parts – a nave and a sanctuary, the interior space has a three-part scheme, like all temples of that time. Passing through the main portal, we enter the first space, which is formed by two columns supporting the choirs – this is the narthex. This part in the early Christian churches was reserved for the 'announced' or penitents – people who were going to become Christians. They could listen to the Word and, embodying it, show by their lives the desire to be Christians. That is, it was about the fact that Christ's teaching is not an exercise for the intellect, but a guide to action. It is obvious that at the time the Horiany community was formed, this tradition no longer existed, because after the baptism of children had begun, the practical need for narthex disappeared, but its symbolism remained relevant – it is the external, profane world (opposite to the sacred).

The next part is the nave (from the Greek language 'naos' (ναός), which means ship) is a sacred space. It is this part of the temple that serves as a place of the Christian meeting. After all, the image of the ship is closely related to the history of salvation, because it symbolizes a place that saves a person from a flood, from an ocean of agitated emotions and passions. The ship as a symbol was well understood by people whose thinking was shaped mainly by the Bible, acquiring a polysemantic meaning. This is also the boat from which St. Peter went out during the storm to meet Christ; this is also Noah's ark, in which all living beings were saved during the flood; along with that, this is also the ark in which the stone tablets that Moses brought from Sinai were stored. In the understanding of Christians, this is the place where Christ is present in accordance with his words: 'where two or three are gathered in my name, there I am in their midst'.

Sanctuary is the third section of the temple. In this case, it is a separate round building – a rotunda, to which a nave was later added. In early Christian churches, the sanctuary was built in the form of an apse – a semicircular niche covered with a concha – the half dome. This form was due to the symbolism of the apse – it is a cave, a grotto, the darkest place on earth. In order for the light to get here, there must be some intrusion from the outside – someone with a torch, for example. This grotto is a symbol of the cave in which the light – Christ was born, and it also has the symbolism of the tomb where the dead body of the Savior was laid and from where He resurrected. In a figurative sense, the apse, as the darkest place in the temple, was compared to the human heart, which remains the darkest place for ourselves. Nothing can enlighten it, but the word, which has the ability to penetrate to it.

This symbolism was an important factor that determined the shape and structure of every temple of that time. At the same time, this symbolism determined the composition of the paintings, which emphasized the symbolism of the entire building. It is obvious that the church in Horiany also bears the imprint of the medieval Christian worldview.

Rotunda

Today, the rotunda (round church) is only a small part of the entire church building, although earlier, in the 13th century, it was a family temple, or rather, a family chapel. As we can see from history, Christianity north of the Alps was adopted mainly by the rulers and nobility of various nations, who thus joined the Mediterranean classical culture and education, and later their subjects followed. Those were lords who started the process of building sacred buildings: first for themselves, and later, for example, for monasteries. We can consider the Horiany Rotunda as one of such temples, built for the religious needs of the powerful Aba magnate family. In the southwestern part of the sanctuary we notice a bricked-up semicircular portal with a small triangular pediment above it, which proves the building was a separate temple retaining signs of Romanesque construction.

The very shape of the temple is quite interesting: six niches-apses with conchae were embedded in the massive wall of circular floor plan, thus resembling a six-petalled flower. A hexagonal drum topped by a dome rests on the inner protrusions between the apses. In this way, we get a very interesting centric dome structure. Six windows that cut through each side of the hexagonal drum were the main source of light in this structure. Looking for analogues we come across buildings in the villages of Kiszombor and Korcso in Hungary. The ground plans of these structures are almost identical to that of Horiany rotunda, but their construction has notable differences. Thus, in Kiszombor, the internal protrusions of six apses became supports for Gothic ribbed vaults, which are authentic to this structure. The vault in the Korcho rotunda is similar. The round structure is covered by a baroque vault, which in its shape is very similar to the Gothic vault in the Kiszombor rotunda. Unlike Horiany, the walls of both temples are cut through by several windows, and they also have external architectural decoration in the form of pilasters or half columns. Despite the similarity of the plans of the mentioned buildings, there is a noticeable difference between them in the formation of the vaults.

Many researchers sought the origins of the Horiany Rotunda in the East, that is, in the Middle East. Such visions are quite reasonable, because it is here in Palestine that St. Helen and St. Constantine built the first two round churches: the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity of Our Lord in Bethlehem. From the history of architecture we know that round temples were built as important memorial places or baptisteries. Among the sources, where the origins of the Horiany rotunda were sought, churches in Armenia were singled out, in particular the Church of the Holy Redeemer from Ani (territory of modern Turkey), which has the form of a dome temple with eight conchae. This structure has been preserved only partially. However, the question of the ways of penetration of these architectural forms into Europe remains open. Some historians looked for an answer in the activities of the knightly order of the Joannites. King Géza II actively supported them in Hungarian kingdom, and his wife Euphrosynia, the granddaughter of Prince Volodymyr Monomakh of Kyiv, gave the order property in the vicinity of Satmar, where, by the way, the round church from Korcso also belongs.

However, not so long ago in Romania, on the territory of a former medieval monastery in the city of Cluj, the foundations of a round structure with conchae embedded in the wall were found. This find is very important, because it can change the search vector to the south – to the Balkans. In our opinion, the role of the Balkans in the process of Christianization of the Carpathian basin is far from being studied. Therefore the views of W. R. Zaloziecky, who indicated the possible Balkan sources of the Horiany rotunda, make sense. Taking into account the concentration of six-concha and eight-concha buildings in Dalmatia, we can consider it to be such a center. In particular, the church of the Holy Trinity with six conchae in the city of Zadar dates back to the end of the 8th – the beginning of the 9th century. Especially expressive is the hexaconcha shape in the preserved part of the church of St. Michael in the city of Prydraga (Croatia), which is attributed to the second half of the 9th century. The remains of the hexaconcha church of the 9th–11th centuries in the city of Trogir (Croatia) and, perhaps, the best-preserved Holy Trinity church in the city of Split are included into the same group of temples.[2]

Taking into account the above and the processes of the spread of Christianity from the south to the north, we can assume that it is the southern vector in the study of the origins of the Horiany Rotunda that can give the most interesting results. In turn, the Horiany Rotunda has a great cultural and historical significance, because it symbolizes the interesting, and still far from explored ways of the penetration of Christianity into the Carpathians together with the achievements of Mediterranean architecture. We can also assume that the construction of the round temple in Horiany, probably by the magnate Amodé Aba, can testify to the great importance of this place for the mentioned family.

Painting

Several stages of frescoes are preserved in the rotunda. The oldest wall paintings have distinct Romanesque features and may belong to the end of the 13th century when rotunda was constructed. The next wall painting in the three eastern apses was created in the time when the rotunda became a sanctuary of the temple, most likely in the 14th century. The last series of the painting was performed in the 15th century as an important content element of the nave space. It bears noticeable signs of Gothic painting, which is especially evident in the compositions 'Crucifixion of the Lord' and 'Annunciation'. Thus we can see that the development of painting stages in Horiany is quite similar to Italian artistic processes: after the Romanesque style, painting with noticeable signs of the Proto-Renaissance appears, and everything ends with Gothic.

Romanesque features are noticeable in the paintings of the northwestern apse: 'St. George the dragon slayer' on a horse and the remains of a wall painting, in which the figure of a bearded man with a nimbus above his head can barely be seen. In these remains the silhouette of a man wearing red boots and a robe with a decorated hem can be guessed. Taking into account the iconography, the Hungarian researcher József Lángi assumed that it is the figure of St. Nicholas. Especially expressive is the image of St. George the dragon slayer: the schematic posture, the angular lines of the cloak silhouette, the planar interpretation and the characteristic modeling linearity point to the aesthetics of the Romanesque era, which prompted us to associate these paintings with the 13th century[3]. This dating is consistent with the history of the appearance of the St. George on horseback iconography in Europe, which took place in the 12th century. This cult was brought by the Crusaders from Syria, and its popularity in the West was helped by the work of the Dominican monk Jacobus de Voragine 'The Golden Legend', published in 1260.[4]

The paintings of the drum and the dome have been studied the least. Probably, they belong to the first stage of the temple decoration. A visual inspection of the painting remains gives reason to talk about the twelve apostles painted there: faint silhouettes of the figures can be seen – two figures above each wall of the hexagonal drum. If we assume that in the central part of the dome there was an image of Christ Pantokrator, then this can be considered a peculiar embodiment of the Byzantine painting canon, which was formed in the 9th century as a pattern for cross-domed churches. Seen between the figures of the apostles grouped in pairs, are ornamental motifs, reminiscent of a folk decorative element, the so-called 'vase' or the popular 'palm' motif.

The complex of paintings of the second stage are usually dated to the 14th century[5]. In their manner the signs of the Italian Proto-Renaissance can be traced. These paintings are mainly associated with the Drugeth family, which at that time held important positions at the royal court. Among them were the court marshal Wilhelm, and later – Nicholas I, John III and Nicholas III, who owned Horiany. This assumption gives grounds for a more accurate dating of the paintings in the rotunda. In particular, it is associated with the return of Nicholas I Druget in 1354 from Italy. A rather interesting dating is provided by the famous Ukrainian art researcher Hryhoriy Lohvyn, who believed that the style of painting in Horiany resembles the works by Tyrolean or Italian artists in 1367 after the fire in rotunda.[6]

These frescoes show the artist's desire to use linear perspective in the construction of space and to treat figures combined into genre scenes in a three-dimensional manner, which is a characteristic feature of painting that appeared in the Proto-Renaissance period. The figures wear clothes of everyday life, which indicates new aesthetic orientations in church art. The Italian origin of the author can also be indicated by the iconographic features of the painting, for example, in the form of the composition 'Thronum Gratie' ('Throne of Grace'), fragments of which are preserved in the south-eastern concha of the rotunda. The remains of this composition allow us to say that here is an image of God the Father, who supports the cross with the crucified Son in his hands, and flying from his mouth is a dove – a symbol of the Holy Spirit. The composition reminds us of Masaccio's work, performed in 1427 in Florence.

The logic of pictorial scenes gives reason to believe that the frescoes of the second half of the 14th century were painted on walls that, most likely, were not previously covered with paintings. The integrity of the composition design is evidenced by the thematic accents, with the help of which the artist tries to reveal the idea of salvation through the Church. In Horiany we are dealing with a complete three-tiered composition that occupies three apses and has an ornamental frame. The author does not divide the scenes in each tier into separate fields with the help of frames, but leads a consistent narrative, focusing on the most important points of the presentation. Two storylines have a logical beginning and ending, despite the inclusion of some chronologically illogical scenes. This allows us to say that there were no other parts of the painting that would be considered lost. The images of the third tier are made in conchae. The author presented the main idea of the images in two tiers below the conchae. They are thematically divided into scenes depicting the incarnation of the Son of God – in the upper tier and redemption through Christ's suffering – in the lower one.

The concha of the eastern apse contains the image of Christ the Almighty in a blue chiton. Around him we see four half-figures of angels and the sun and moon in the form of male and female heads. Hungarian researcher Jozsef Huska made sketches of angels with tapes in 1900. He recorded the opening sentences of four gospels written on each tape in Latin, and this gives reason to interpret the figures as evangelists. Depicted in the concha of the north-eastern apse, is the Mother of God with the baby Christ and two angels kneeling with candles in their hands. The south-eastern concha has considerable loss of painting, to the right of the figure of Christ, less than half of the wall painting has been preserved. However, the remains of this composition make it possible to identify the scene as the 'Throne of Mercy' with the monk in the Franciscan clothes.

The stories on the walls are arranged in the following sequence: 'Annunciation', 'Christmas of the Lord', 'Gifts of the Magi', 'Herod orders the extermination of the babies', 'The killing of the babies in Bethlehem', 'Flight to Egypt', 'Holy Family', 'The Last Supper' in the upper tier; 'Prayer for the cup', 'Peter cuts off the ear of the slave', 'Kiss of Judas' in the lower one. Then there is the 'Coronation of Mary' composition, which can be explained only by some liturgical visions of the customer or the artist, since its presence in the passion cycle is strange. This scene is followed by the compositions 'Christ before Pilate', 'The scourging of Christ', 'The carrying of the cross', 'The crucifixion', and 'The resurrection of Christ'. The last composition is especially interesting, because Christ ascends over a hexagonal tomb, which should perhaps be connected with the shape and symbolic meaning of the rotunda itself as a sanctuary. The drawing of the southwestern apse can be better judged on the basis of József Huska's drawings in 1900.[7] One of the compositions is 'Washing of the Feet of Christ', where two female figures could be viewed through the 'Parable of Mary and Martha', and the next depicted two women with halos. One of them (with roses) is most likely St. Elisabeth. These images appeared later, when the portal of the rotunda was bricked up. A panel decorated with curtains motif passes under the three eastern apses at a distance of one and a half meters from the floor.

The compositions are much more interesting to read if they are considered in the context of each apse. The combination of the scenes of the upper tier and the lower one gives a somewhat new reading of the compositional idea of each of the apses. Thus, in the first apse we see the theme of the birth of a baby from the royal family of David, which in the lower tier of the scene of the Lord's passion ends with the 'Coronation of Mary', where Christ also has the royal wreath. Mary with Jesus are depicted above this painting, in the first concha, Jesus, has a crown, as an image of the glorified Church. Thus, we can interpret the compositions of this apse as the idea of accepting the will of God, which leads to salvation and the Kingdom of Heaven. Therefore, it is not by chance, that in this apse we see a distinct emphasis on the presence of God in the lower and upper tiers.

In the upper tier of the next apse, the first fresco depicts Herod and the scene of the killing of innocent babies. The problem of power as such, which leads to positive or negative consequences, is acutely apparent in the central apse. This topic of power and court is very important, because it was this activity that the representatives of the Druget family were engaged in at the Hungarian royal court. Human judgment is clearly revealed through pictorial scenes: the upper tier ends with the 'Killing of the Infants in Bethlehem,' and the lower one – with the 'Carrying of the Cross.' At the top of this apse is an image of a blond Christ in the form of Pantokrator, who represents the presence of God and who is the one who holds the whole world.

In the last apse the Last Supper is depicted in the upper part. This scene actually presents an image of the Eucharist, and therefore the birth of the Church. We can say that this apse is a form of response to suffering by a meal of love. Painted below this scene are the compositions of the crucified Christ and the Resurrection of the Lord. In fact, the mystery of the breaking of the body and its transformation through resurrection is revealed – the sowing of the earthly so that the heavenly is born. The last apse became a kind of quintessence of the rotunda painting system. Here, in the concha of the apse, the already mentioned composition 'Throne of Grace' is presented. It reveals to us the great love of the Father for a man: 'For God so loved man that he gave his only begotten Son for him'.

Basing on the given facts: the framing of the three apses with a common ornament; the thematic logic of the depicted compositions not only horizontally, but also vertically; the image of Christ the Almighty in the central apse complemented with two additional ones – Crowned Mary with Christ and the New Testament Trinity, we can say, that we see a peculiar form of the Latin three-part altar, which began to develop especially actively in the 14th century.

They construction of the nave in the 14th century caused the appearance of three compositions here. They are 'The Annunciation', 'The Protection of the Virgin (Theotokos of Mercy)' and 'The Crucifixion of the Lord'. By the manner of painting, these works are markedly different from the compositions of the 14th century. 'Annunciation' reflects the trinitarian teaching in the image of the Trinity: God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit. Such an image is quite rare, because the artist tries to present the idea of the Trinity clearly, without any allegories. Under this scene, the image of the 'Protection' is presented, which is based on the Western European iconography of the Madonna of Mercy. This composition reveals the image of the Church, we see the pope, Christian kings, cardinals, priests and the people of God. The fresco also depicts an angel who brings some people out from under the veil. The third composition 'The Crucifixion of the Lord' depicts the crucified Christ and two figures below. The artist emphasized Maria's suffering – she fainted on the fresco. After all, Gothic conveyed the emotional tension of the depicted scene through facial expressions and gestures.[8] The ornamentation and manner of painting lead to the idea that the master was closely connected with the artistic centers of the north of Austria or the south of the Czech Republic or even could come from there.

The Horiany Rotunda presents a unique complex of architecture and painting, which reveals the development of cultural processes starting from the 13th century until today The monument is an important cultural and historical factor that connects us with important processes of the development of European culture and our history.

History

The first documentary evidence of Horiany is found in the charter of Amadeus Aba (Obo), who owned a huge territory in the north-east of the then Hungarian kingdom, which included the counties of Zemplin, Ung, Bereg and Szepes. In the 1280s, he allocated the Nevitsky manor together with Horiany from the lands that were the property of the Uzhhorod castle, and in 1288, kng Lászlo IV granted Amodeus the entire Ung county. In 1334 and 1335, the village of Horiany was mentioned as a parish that paid the papal tithe[9]. In the 16th century the painting was overlaid with a new plaster, which should be connected with the reformation movement, whereas in the 1540s the Druget family took under their care the Protestants of Uzhgorod,[10] and accordingly, the surrounding areas. However, in 1609 Wilmos Druget died, and three years later his son also died. The result was that count George III Druget, the owner of Ung and Zemplin counties converted to the Catholic church, and in 1644 Horiany and the church already belonged to the Catholic denomination.[11]

The last changes that determined the modern appearance of the church took place in the 18th century, when a small baroque tower was erected on the western facade. Historical facts show that from the middle of the 17th century the church functioned as Roman Catholic. According to Uzhhorod historian Yosyp Kobal, in 1754 the Uzhhorod administrator baron Imre Starai handed over the temple to the Greek Catholics, who at that time constituted the majority in Horiany. However, in the 19th century the temple was mentioned as Roman Catholic. It is interesting that in 1945, the Soviet authorities again returned the church to the Greek Catholics, but only with the aim to liquidate this denomination in 1949, and transfer the rotunda to the Moscow Orthodox Church.[12] The church functioned until 1959, when during a storm the building was struck by lightning, causing casualties among the faithful. The Soviet authorities took advantage of the moment and closed the church. Later, work was carried out to clean and restore the frescoes, and in 1966 a branch of the Transcarpathian Regional Museum of Local History was opened here. Since 1991, the Horiany Rotunda is a functioning Greek Catholic Church of the Protection of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Despite some ill-advised interventions, the rotunda has become one of the most visited sights of Zakarpattia, attracting considerable interest of both scientists and numerous tourists.

Read More

Do you have any questions for us?

Contact Usmob: +380 (96) 762 29 19

e-mail: